On January 26, 2018, it was announced that the Canadian Government had contributed $3.5 million to the Canadian Naval Memorial Trust (CNMT) for repairs to

HMCS SACKVILLE, the last remaining

Flower-class corvette. These once numerous ships escorted convoys across the North Atlantic during in the Battle of the Atlantic, attempting to keep them safe from German U-boats. Now, only SACKVILLE remains, and she is showing her age.

The work will be carried out by the Navy's own forces, using the Syncrolift hoisting platform and the new Captain Bernard Leitch Johnson submarine maintenance building (part of Fleet Maintenance Facility Cape Scott) within HMC Dockyard. Wasting no time, the Navy and the CNMT had SACKVILLE reballasted and ready to move on the morning of Sunday, February 12, on a "Fine Navy Day" (1). I was dressed in rain gear, and had to use a combination of an umbrella and several rain covers to keep my cameras dry. The tugs arrived at 6:40am.

|

| Tugs Merrickville (foreground) and Glenside (background) approach SACKVILLE. |

|

| SACKVILLE was tied up near the south end of HMC Dockyard, and needed to be moved north to the Syncrolift. |

Lines were quickly made fast to the tugs, and things were quickly underway.

|

| SACKVILLE pulls away from the jetty. Her mast has been cut off because it would have hit the top of the sub shed when she is moved inside for her refit. |

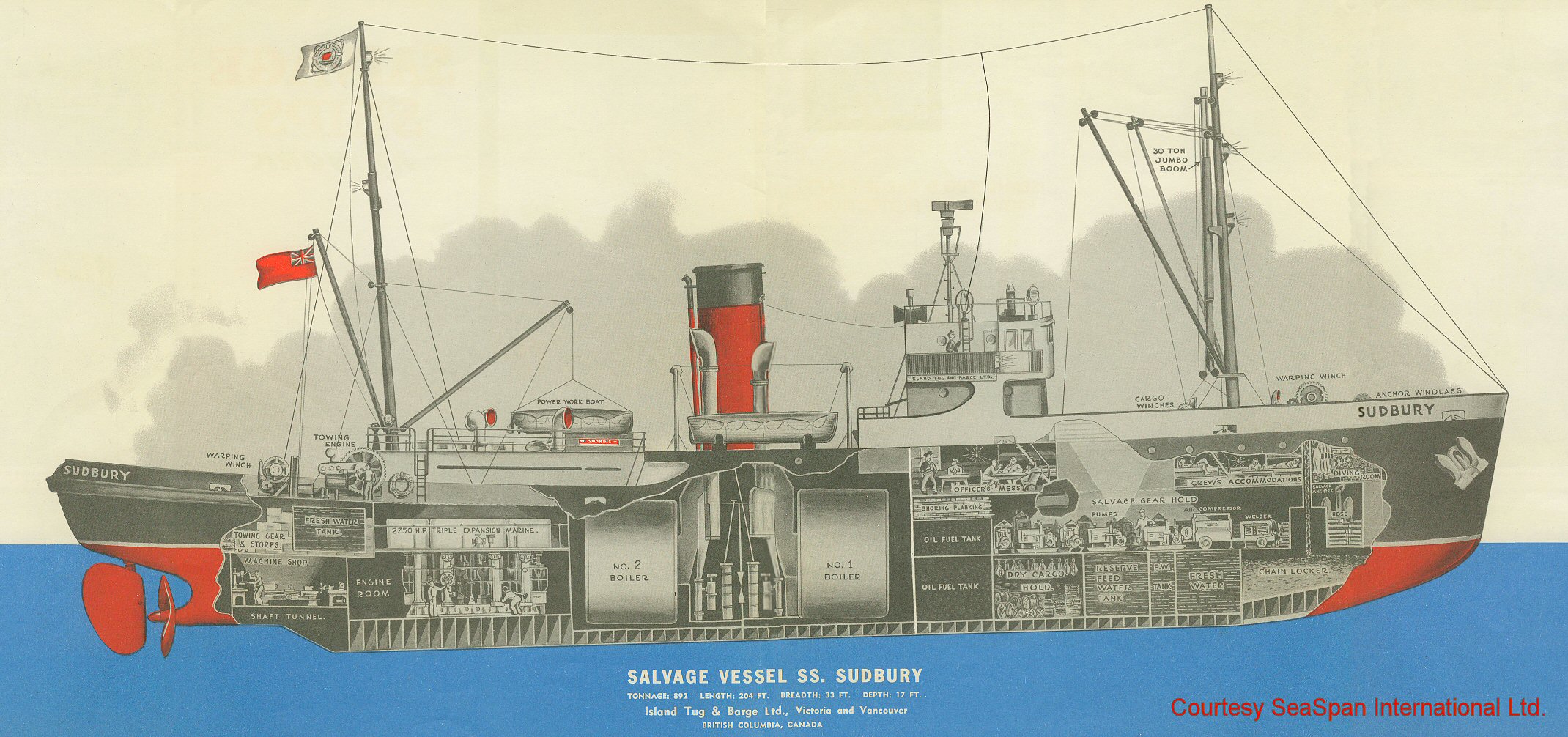

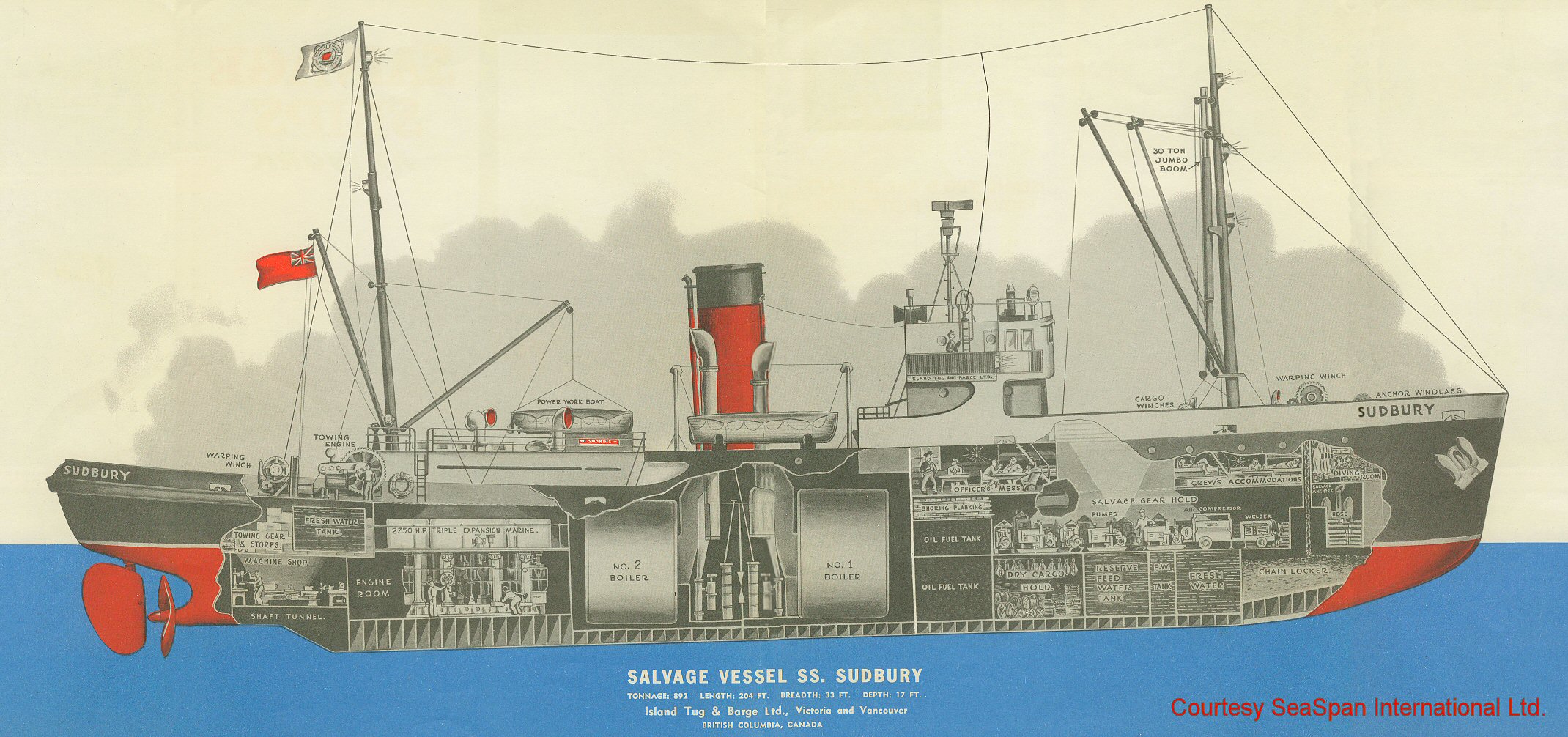

The keel line of Flower-class corvettes slopes deeper as it goes aft, and on a properly trimmed corvette the keel is not horizontal.

|

| This cutaway view of S.S. Sudbury, a salvage tug converted from a Flower-class corvette, nicely illustrates the sloping keel. (Courtesy SeaSpan.) |

The keel blocks on the Syncrolift, however, are

horizontal. In the days before the move, SACKVILLE's mast was removed (to allow her to move into the submarine shed) and she was retrimmed fore-and-aft to lower the bow and raise the stern, to level out the keel line.

|

| This is a good view of the retrimming required to prepare SACKVILLE for the Syncrolift. |

|

| The tow proceeds around the bow of HMCS MONTREAL. |

At about this point in time, I ran north to catch SACKVILLE as she rounded the end of the Syncrolift piers. A product line currently owned by Rolls Royce, a

Syncrolift is a hoisting platform slung between two fixed piers by a series of winches and cables, and the winches can be operated in synchronization (hence the name - minus the "h") with each other to lift and lower the platform on an even keel.

|

| Tugs easing SACKVILLE in between the Syncrolift piers of Jetty ND. |

The HMC Dockyard lift was originally constructed in 1967 to hoist OBERON class submarines out of the water for maintenance, and in 1970 a shed was constructed at the inshore end of the Syncrolift to allow these submarines to be moved ashore and into the shed so they could be maintained and refitted out of the weather. The old submarine shed wasn't perfect - the sliding doors had to actually be removed from their rails to allow an O-boat to enter, and it was fairly tight quarters. The old shed was replaced with new building during the 2000s, which I will cover in the next post.

Starting in the 1984, the Syncrolift was lengthened by 33 metres and modified to lift a ship of "NATO frigate" size - this included the Navy's IROQUOIS-class destroyers and the then-future HALIFAX-class frigates which displaced in the range of 4500-5000 tons (but I have seen one source indicating the upgrade would allow the Syncrolift to hoist up to a 6,000 ton ship). This also involved strengthening the lifting beams under the ship's machinery spaces (the heaviest portion of the ship), and upsizing the associated winches.

|

| A wider angle version of the image above. The blue objects lining the piers are the covers over the Syncrolift winches. |

|

| There is enough room for the tugs to remain alongside SACKVILLE as they bring her in. |

|

| The water surface over the Syncrolift platform was smooth and provided a nice reflection of the hull. |

|

| SACKVILLE is almost in position, but needs to be straightened out and aligned with the support blocking. The first positioning line can be seen running off the bow. |

|

| SACKVILLE now straightened out, with more positioning lines running to the piers. I love the reflection in this shot! |

|

| Once SACKVILLE was judged to be in position, the lift platform was brought up a bit, and divers were put into the water. |

|

| The view from inside the Submarine Maintenance Building, during a break while the divers checked on SACKVILLE's positioning over the support blocking. The rails run from the platform all the way into the shed, to allow submarines and other small vessels to be brought in for maintenance. Though they can be hoisted on the lift itself, major surface warships, and even the smaller MCDVs, need not apply. |

|

| Three divers in the water. |

|

| The divers were operating from a RHIB (Rigid Hulled Inflatable Boat). This shot shows some of the ropes holding SACKVILLE in position over the blocking. |

|

| The end of the line - until the platform comes up anyway, and then the rails will continue out onto the platform. The yellow bollard in the foreground is an anchor point for the tow motor inside the shed (details of which I will save for another post). |

|

| Divers have confirmed SACKVILLE's positioning over the support blocking, and the Syncrolift platform has started to rise and lift SACKVILLE out of the water. SACKVILLE is sitting on the blocking in this photo. |

|

While doing their inspection, the divers noticed that the ship was still trimmed with the bow down a bit as compared to the blocking, Correction: Once the divers confirmed SACKVILLE was firmly on the blocking, a pump was rigged to empty the approximately 45-50 tonnes of water from the forepeak that was used to trim the bow down. You can see a hose discharging water from the port bow. |

|

| The Syncrolift is hoisting SACKVILLE and the tops of the bogeys on which the blocking is installed are starting to emerge from the water. |

Flower-class corvettes were known for two things in particular: they were very lively ships in a sea (and were reputed to "roll on wet grass"), and they were the only escort ship that could turn inside of a U-boat. I think SACKVILLE's poise in the above photo speaks to both attributes.

|

| The Syncrolift platform is almost all the way up, and the wood decking of the platform is fully visible. The weight of the ship rests on the blocking, which in turn sits on the rail bogeys, which in turn sits on the four rails that run from the platform into the building. |

|

| The workers standing on the platform provide some scale to the image - the corvettes may have been small, but they still look big when they are towering over you on the Syncrolift. |

|

| SACKVILLE on the lift, with the Captain Bernard Leitch Johnson submarine maintenance building in the background with the doors slightly open. |

|

| The raised blocking under the forefoot, and the bogeys upon which it rests, was wheeled out after the lift was brought all the way up. |

|

| SACKVILLE's propeller was removed years ago, and only the shaft remains in place outside the hull. The single rudder seems fairly large to me, and placed immediately aft of the single propeller, would have contributed to the corvette's tight turning circle. |

|

| The starboard bilge keel and some of the remaining marine growth. In addition to barnacles, starfish, and mussels, the orange things hanging from the hull in this picture were plentiful and have apparently only appeared in the harbour since the end of the Harbour Cleanup project - I'm not sure what they are. The fin in this photo is the bilge keel, which was pretty much the only thing fitted to combat the legendary corvette roll. Based on the corvette's reputation, it was insufficient. The bilge keep is lined with anodes, which are fitted to prevent underwater corrosion of the ship's hull - SACKVILLE has many more of these fitted now that she would have had while in service. |

|

| A look along the hull from the after starboard side, better showing the some of the marine growth, bilge keel, and blocking. The blocking itself is laid out based on plans of the ship. A couple of us came up with the brilliant theory that the orange growth was primarily around the engine and boiler rooms, and perhaps these spaces were warmer and encouraged the growth - only to be informed that divers had removed much of the growth prior to being put on the lift. |

|

| To my mind, this starfish can only be described as "lounging". In fact, I think it is kinda creepy. |

|

| The bogeys and blocking under the forefoot were wheeled into place after the ship came out of the water. The stair tower is on wheels, and was towed out by a forklift. |

|

| The two sets of rails upon which the bogeys ride. Bogeys can (and do) straddle either of the sets of rails on the left or right, or the set in the middle. |

|

| The view from the stair tower. The end of the wooden-decked platform can be seen where it transitions to the concrete surrounding the rails in front of the shed. |

|

| A crane has placed the brow from the stair tower to the foc'st'le. |

|

| SACKVILLE prior to cleaning. |

Before SACKVILLE is brought into the maintenance building, her hull needed cleaning, and workers used high-pressure water to blast the marine life from the hull. It is preferable to do this while on the lift, rather than inside the building, for obvious (and smelly) reasons.

|

| SACKVILLE after cleaning. |

|

| Exterior lights on the Syncrolift piers illuminate SACKVILLE while the sun sets in the background. |

SACKVILLE was moved into the maintenance building on the morning of Thursday, February 15, which I will cover

in a separate post.

A complete gallery of my processed images of SACKVILLE's lift and transfer is

linked here.

Notes:

(1) As these things are usually planned well in advance, and it is not possible to reschedule the complicated array of resources required to make it happen, it is inevitable that sometimes these events happen in the rain. In the cold of February. I'm told this is "Fine Navy Weather", to which I respond "If the Navy likes it so much, they should keep it to themselves, and not inflict it upon others." That said, I only had to take photos, and didn't have to handle lines, insert blocking, or dive under the ship to make sure it was in the correct location. So I shouldn't complain too much.

(2) For those that wonder about the title that I chose for this blog post, I am unaware of any actual drunken sailors being involved in the docking of SACKVILLE.

Sources:

Some of the Syncrolift data and upgrade information and dates are from the 1985 edition of "Canada's Navy Annual", in an article named "Changing Face of the Dockyard" by Thomas Lynch.